History Of The Shawnee: Part 1

Piqua Shawnee officially recognized American Indian Tribe by the State of Alabama.

Exhibit: September 21, 2014–2021

Washington, DC

From a young age, most Americans learn about the Founding Fathers, but are told very little about equally important and influential Native diplomats and leaders of Indian Nations. Treaties lie at the heart of the relationship between Indian Nations and the United States, and Nation to Nation: Treaties Between the United States and American Indian Nations is the story of that relationship, including the history and legacy of U.S.–American Indian diplomacy from the colonial period through the present.

Generous support for the exhibition is provided by:

http://www.nmai.si.edu/explore/exhibitions/item/?id=934

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Shawnee tribal leader Charles Bluejacket carved this walking stick for his friend Charles Boles, a Methodist missionary, in the mid- to late-19th century. The two met in Kansas in the early 1850s, when the church assigned Boles to preach to the Shawnee tribe.

A deep friendship took root between two men in the wilds of Kansas. Their bond spanned the differences of culture and race, and lasted a lifetime. Today we often think of encounters between whites and American Indians on the frontier as tense, even violent. This was not always the case. The likelihood that individuals would get along depended on their personalities and as well as the circumstances under which they interacted. In this regard, Bluejacket and Boles may have been predisposed to friendship. Both men were deeply religious. They fathered large families, and lived respectable lives by European-American standards.

Charles Bluejacket came to Kansas as a youth after a treaty with the United States government removed the Shawnees from Ohio and Missouri. His grandfather was the famous chief Bluejacket, and his grandmother probably was white. Charles was familiar with Indian missions, having attended a Quaker school in Ohio. In Kansas, he completed his education at another mission school. He married, became a successful farmer and interpreter for the federal government, and began leading a prayer group.

Charles Boles converted to Methodism as a young man in Missouri and was ordained an elder in 1851. The following year he was assigned to the Shawnee Indian Mission School in present-day Kansas City. It was during his six-year ministry to the tribe that he became friendly with Bluejacket.

Conditions were primitive at many frontier missions, but not at Shawnee Indian Mission. The Methodist church considered it an exemplary site, as did the federal government (a major funding source). At its height, the mission occupied almost 2,000 acres, much of it farmland. Its grounds had brick schoolhouses and dormitories, workshops, and farm buildings. Because the Methodists used “circuit riders” (traveling ministers) to spread the gospel, Shawnee Mission was Boles’ headquarters, although he spent most days in the field ministering to his flock.

Details on the friendship between Boles and Bluejacket are spotty, but the two men obviously saw each other frequently and perhaps even rode the circuit together. One early visitor to the area noted that he met Bluejacket and Boles at another missionary’s home in 1857. The Methodist conference minutes for this time period record that Boles was “assisted” by Bluejacket and others in building the church rolls to about 100 Shawnees.

Details on the friendship between Boles and Bluejacket are spotty, but the two men obviously saw each other frequently and perhaps even rode the circuit together. One early visitor to the area noted that he met Bluejacket and Boles at another missionary’s home in 1857. The Methodist conference minutes for this time period record that Boles was “assisted” by Bluejacket and others in building the church rolls to about 100 Shawnees.

The six years Boles preached to the Shawnee tribe coincided with the Bleeding Kansas era, when violence exploded along the Kansas-Missouri border. It became extremely difficult to accomplish any missionary work. The Methodist conference minutes for this period note, “There was comparatively little done from 1855 to 1865. During these perilous years Bro. Boles stood almost alone.” Almost alone, but not quite. His friend Bluejacket had become an ordained minister in 1859. When war made it impossible for whites to preach at Shawnee Mission, Bluejacket became missionary in charge.

A number of mission schools closed during the Civil War, including Shawnee Mission. Methodists continued to preach to the tribes remaining in Kansas, but most American Indians were removed to Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) shortly after the war. Boles began preaching to non-Indian Methodists in eastern Kansas. Bluejacket became a prosperous farmer, despite the fact that many of his fellow tribesmen had moved south. An 1874 county atlas describes his “beautiful farm” and house “furnished in a style that would do credit to many of our wealthy people.”

Bluejacket eventually joined his tribesmen in Indian Territory, but before he left he made this elaborate walking stick for Boles. Its carved figures include at least two motifs from the pillars of an early Shawnee council-house in Kansas–a rattlesnake and a turtle, the latter being prominent in Shawnee creation mythology. View a close-up of the turtle carving. The walking stick was passed down in the Boles family until the Kansas State Historical Society acquired it in 2009. It is in the collections of the Society’s Kansas Museum of History.

Entry: Walking Stick

Author: Kansas Historical Society

Author information: The Kansas Historical Society is a state agency charged with actively safeguarding and sharing the state’s history.

Date Created: July 2009

Date Modified: December 2014

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

The Shawnee Indians, also of Algonquian stock, lived in the east and Midwest. Their first contact with white men came in the 1600s. Early estimates of their population range from 3,000 to 50,000, although 10,000 appears to be the most probable estimate. Shawnee comes from the Algonquian word ‘Shawun’ (shawunogi) meaning ‘southerner.’ The application of southerner is indicative of their location vis-a-vis the other Algonquian tribes who lived to the Shawnee’s north, around the Great Lakes. A symbol of the Shawnee authority is the eagle feather headdress.

During the 1600s, they were forced to leave their traditional lands, including the Ohio Valley, by the marauding Iroquois during the Beaver Wars. In the 1700s, they once again began to call the Ohio Valley their home, settling initially along the Ohio River where conflict with white settlers became a routine occurrence. Allying themselves with the British during the Revolutionary War, combined with being absolutely against white expansion beyond the Appalachian Mountains, did not endear them to the Americans. Led into battle by Chief Cornstalk, they were severely defeated by colonial troops in 1774 in the area of Point Pleasant, West Virginia.

The loss resulted in a split in the Shawnee tribe that caused many of them to move west beyond the Mississippi River. Those that stayed behind in Ohio rallied behind Tecumseh until the 1811 Tippecanoe defeat and the death of Tecumseh in Canada during the War of 1812.

The Shawnee village of Piqua (Piquea), located four miles southwest of Springfield, Ohio, was attacked by American soldiers under the command of General George Rogers Clark on August 8, 1780. It was a ferocious battle that ended with the total destruction of the Shawnee village, and their agricultural crops.

Seeking a new area in which to build a village, the Indians traveled northwest until they reached the Great Miami River where they chose a location on the west side of the river, just north of where the Johnston Indian Agency would eventually be constructed. They named this new village, upper Piqua. The Miami Indians village of Pickawillany, along with Fort Pickawillany, was at this same site until it was abandoned in 1763 after an earlier unsuccessful attack by the Shawnee.

At the same time, they established another village in the area, on the east side of the river, on a site that is now occupied by the city of Piqua. The Shawnee named this second village lower Piqua. They had lived in the Piqua area for two years when, in 1782, General Clark and 1,000 Kentuckians moved north into Ohio. The Shawnee decided to abandon their Piqua villages without a fight and moved to a location on the Auglaize River. After the Greene Ville Treaty was signed, they moved back to the area, locating villages in Wapakoneta, north of the new treaty line, Hog Creek (southwest part of Lima) and Lewistown.

In 1832, they ceded the last of their Ohio lands to the government, and in a sorrowful procession through Hardin, Piqua, Greenville and Richmond, the last of the mighty Shawnee rode their horses to a new home in eastern Kansas.

Today, most of the Shawnee live in Oklahoma or have merged into this region’s population. A monument can b e seen today in the small park area in Hardin, six miles west of Sidney, at the intersection of State Route 47 and Hardin-Wapak Road. It is located on the southeast corner of the park. This monument commemorates not only the killing of Colonel Hardin by the Indians, but also marks the spot where the Shawnee camped in October, 1832, on their last trek from Ohio.

e seen today in the small park area in Hardin, six miles west of Sidney, at the intersection of State Route 47 and Hardin-Wapak Road. It is located on the southeast corner of the park. This monument commemorates not only the killing of Colonel Hardin by the Indians, but also marks the spot where the Shawnee camped in October, 1832, on their last trek from Ohio.

https://www.shelbycountyhistory.org/schs/indians/shawnee.htm

‘Indian’ segment written in December, 1997 by David Lodge

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Causes:

The Federal Road divided the traditional Upper Creeks from more assimilated Lower Creeks.

Battles raged on the frontier between Creek “Red Sticks” and American militia led by General Andrew Jackson. The last and most famous battle, the Battle of Horseshoe Bend (now a National Military Park) destroyed the strength of the Creek Nation. General Jackson forced the Creeks to sign the Treaty of Fort Jackson, ceding some forty thousand square miles of land to the United States.

Consequences:

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Halbert, Henry S. and Timothy H. Ball. The Creek War of 1813-1814. 1895. Reprints, edited, with introductions and notes, by Frank L. Owsley Jr., Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama, 1969 and 1995.

In vivid detail, Halbert and Ball recount everything they could find about this conflict. The names of participants (their ancestors and children), locations of battles with full descriptions of gory scenes, and comments on accounts of informants and other writers make this a wonderful source. Students will find textbook accounts of the Fort Mims massacre pale compared to this one. The question of what caused the Creek conflict, whether it was a civil war brought on by factionalism between Lower Creeks and Upper Creeks, is debated.

Holland, James W. Andrew Jackson and the Creek: Victory at the Horseshoe. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1968. Reprint, 1990.

This fifty-page booklet, published to promote Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, offers a concise story of the events that brought an end to the Creek Nation in the South. Students will enjoy this well-illustrated, lively account.

Martin, Joel W. Sacred Revolt: The Muskogees’ Struggle for a New World. Boston: Beacon Press, 1991.

Martin approaches the history of the Muskogees (Creeks) from a religious point-of-view. According to his theory, their “culture of the sacred” determined how they interacted with and reacted to Europeans and, later, Americans. To support his theory, he discusses their spiritual, economic, and social background. He compares their revolt against the Americans in the Creek War with struggles of other native Americans to retain their traditions. It is an interesting theory that can provide an introduction to the religious beliefs of the Creeks.

Wright, J. Leitch Jr. Creeks and Seminoles: The Destruction and Regeneration of the Muscogulge People. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986.

The names Creek and Seminole were attached to the Muscogulge people for the convenience of European and U.S. governments who wanted to address nations. The Muscogulge lived in Georgia, Alabama, and Florida—geographically close, but not unified under one leader. Although some had ancient common origins, many spoke different languages and often could not understand each other. Wright explains the background of the Muscogulges and describes their culture in language readily understood. He defines words that he believes might be unfamiliar to the general reader. He elaborates on familiar topics such as trade, relations with European powers and the U.S. government, the Creek Wars with Andrew Jackson and his pursuit of the survivors into Florida, and finally removal, dispersal, and survival. This book is an enlightening inside view of the Muscogulges’ heroic struggle for survival; it is also an indictment of the U.S. Government.

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

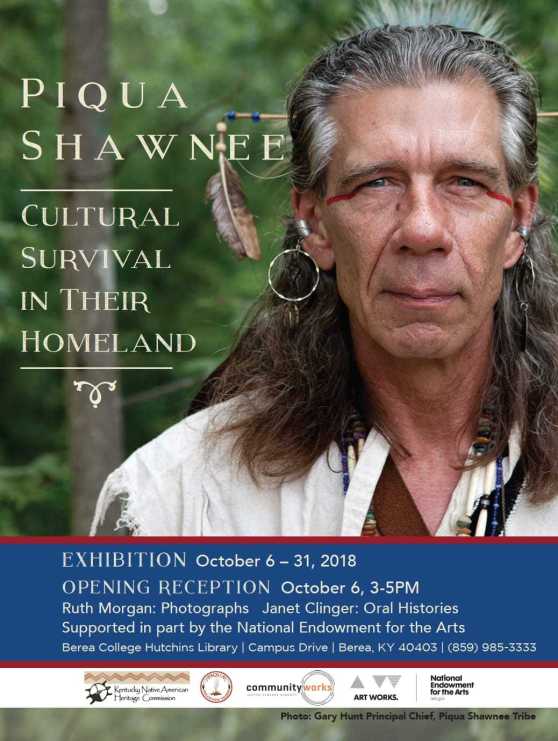

There will be about 30 – 35 framed images with accompanying text. Images are either 20 @20X30” and 12-15 @ 24X36” The topic is the Piqua Shawnee, many of whom live here in KY though the tribe is recognized in Alabama.

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Alabama Historical Commission

NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES

The Fort Mims site commemorates the battle that led to the Creek War of 1813-14.

On August 30, 1813 over 700 Creek Indians destroyed Fort Mims. American settlers, U.S. allied Creeks, and enslaved African Americans had sought refuge in the stockade. The Creek warriors who carried out the attack were members of the Red Stick faction named for the red wooden war clubs they carried. Their assault on Fort Mims is considered one of the greatest successes of Indian warfare.

The Alabama Historical Commission owns this historic site. The Fort Mims Restoration Association is the support group in charge of operating the site.

Visit

https://ahc.alabama.gov/properties/ftmims/ftmims.aspx

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Many Shawnee hoped to remain neutral during the American Revolution, but violence perpetrated by American settlers pushed the Shawnee to the British side. One of the loudest advocates for peace and neutrality was the Maquachake chief, Cornstalk, who corresponded regularly with Congressional Indian agent George Morgan. Cornstalk and other Maquachake leaders were so committed to neutrality that they announced plans to separate their peace faction and found a new town. In October 1777, Cornstalk led a peace delegation to Fort Randolph on the Kanawha River. There he was captured and detained by the fort commander, Captain Matthew Arbuckle. Captain Arbuckle then imprisoned Cornstalk’s son, Elinipsico, who had come to Fort Randolph to inquire about his father’s condition. The Shawnees remained imprisoned through early November 1777, when a party of local militia, seeking retaliation for the death of a white settler, broke into the fort and killed all of the Shawnee under guard, including Cornstalk.

While Cornstalk’s death was officially denounced by Congress, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, Shawnee outrage at the chief’s killing fueled a wave of retaliation and pushed most Shawnee away from the American side, at least during the Revolutionary war. One noted battle that occurred in the wake of Cornstalk’s death was a raid by a Chillicothe war chief, Black Fish, in which he captured Kentucky settler Daniel Boone. Interestingly, Cornstalk’s Maquachakes continued to pursue a policy of peace and neutrality with the Americans and the British. Most of the other Shawnee towns relocated closer to Sandusky and Detroit after the winter of 1777–1778. Beyond a faction of the Maquachakes, led by Chief Moluntha, most Shawnee sided with the British.

After the Peace of Paris, most Shawnee kept the United States at arm’s length. The Shawnee did not join in the Treaty of Fort McIntosh (1785) and resoundingly rejected the “conquest theory” formulation of sovereignty that the Confederation Congress put forward in 1784 and after. While some Shawnee leaders (mostly Maquachake, Cornstalk’s heir as the advocate for peace and coexistence) signed the subsequent Treaty of Fort Finney (1786), the majority still did want a treaty with the Americans. Their forbearance was understandable. As later in 1786, Kentucky militiamen attacked the Maquachake towns and killed chief Moluntha. During the 1790s, the Shawnee formed a large part of the pan-Indian resistance to the federal government led by the Miami chief, Little Turtle. In 1795, the Shawnee signed the Treaty of Greenville, terminating the resistance. However, a minority of the Shawnee, driven primarily by the Kispoki leader, Tecumseh, and his brother Tenskwatawa, would continue the resistance against the Americans until Tecumseh’s death in Ontario at the battle of the Thames River (1813) during the War of 1812. After the War of 1812, the Shawnee were removed west of the Mississippi by the United States government, with most ending up in Oklahoma.

“Shawnee.” Encyclopedia of the American Revolution: Library of Military History. . Encyclopedia.com. 3 Sep. 2018 http://www.encyclopedia.com.

Piqua Shawnee

Piqua Shawnee Tribe

Nonhelema Hokolesqua (Cornstalk’s Sister)[1] (c. 1718–1786) Born in 1718 into the Chalakatha (Chilliothe) division of the Shawnee nation, spent her early youth in Pennsylvania. Her brother Cornstalk, and her metis mother Katee accompanied her father Okowellos to the Alabama country in 1725. Their family returned to Pennsylvania with in five years. In 1734 she married her first husband, a Chalakatha chief. By 1750 Nonhelema was a Shawnee chieftess[1] during the 18th century and the sister of Cornstalk, with whom she migrated to Ohio and founded neighboring villages.

Nonhelema, known as a warrior, stood nearly six feet, six inches(198 cm).[2] Some called her “The Grenadier” or “The Grenadier Squaw“, due to the large height of 18th-century grenadiers.

Nonhelema had three husbands. The first was a Shawnee man.[3] The third was Shawnee Chief Moluntha.[2] She had a son, Thomas McKee, through her relationship with Indian agent Colonel Alexander McKee and another son, Captain Butler/Tamanatha, through her relationship with Colonel Richard Butler.

Nonhelema was present at the Battle of Bushy Run in 1764. She and her brother, Cornstalk, supported neutrality when their land became the Western theater of the American Revolutionary War. In Summer 1777, Nonhelema warned Americans that parts of the Shawnee nation had traveled to Fort Detroit to join the British.[4] Following Cornstalk’s 1777 murder at Fort Randolph, Nonhelema continued to support the Americans, warning both Fort Randolph and Fort Donnally of impending attacks. She dressed Philip Hammond and John Pryor as Indians so they could go the 160 miles to Fort Donnally to give warning. In retribution, her herds of cattle were destroyed. Nonhelema led her followers to the Coshocton area, near Lenape Chief White Eyes.[4] In 1780, Nonhelema served as a guide and translator for Augustin de La Balme in his campaign to the Illinois country.[2]

In 1785, Nonhelema petitioned Congress for a 1,000-acre grant in Ohio, as compensation for her services during the American Revolutionary War. Congress instead granted her a pension of daily rations, and an annual allotment of blankets and clothing.[2]

Nonhelema and Moluntha were captured by General Benjamin Logan in 1786. Moluntha was killed by an American soldier, and Nonhelema was detained at Fort Pitt. While there, she helped compile a dictionary of Shawnee words.[2] She was later released, but died in December 1786.[2]

Foster, Ann (November 22, 2016). “With death on the line, Timeless forges new ground”. ScreenerTV.com. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

The Treaty of Greenville was signed on August 3, 1795, at Fort Greenville, now Greenville, Ohio; it followed negotiations after the Native American loss at the Battle of Fallen Timbers a year earlier. It ended the Northwest Indian War in the Ohio Country and limited strategic parcels of land to the north and west. The parties to the treaty were a coalition of Native American tribes, known as the Western Confederacy, and United States government represented by General Anthony Wayne for local frontiersmen. The treaty is considered “the beginning of modern Ohio history.”[1]

The treaty established what became known as the Greenville Treaty Line, which was for several years a boundary between Native American territory and lands open to European-American settlers. The latter frequently disregarded the treaty line as they continued to encroach on Native American lands.

The treaty line began at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River in present-day Cleveland and ran south along the river to the portage between the Cuyahoga and Tuscarawas rivers, in what is now known as the Portage Lakes area between Akron and Canton. The line continued down the Tuscarawas to Fort Laurens near present-day Bolivar.

From there, the line ran west-southwest to near present-day Fort Loramie on a branch of the Great Miami River. From there, the line ran west-northwest to Fort Recovery, on the Wabash River near the present-day boundary between Ohio and Indiana. From Fort Recovery, the line ran south-southwest to the Ohio River at a point opposite the mouth of the Kentucky River in present-day Carrollton, Kentucky.

The treaty also established the “annuity” system of payment in return for Native American cessions of land east of the treaty line: yearly grants of federal money and supplies of calico cloth to Native American tribes. This institutionalized continuing government influence in tribal affairs, giving outsiders considerable control over Native American life.[2]

In exchange for goods to the value of $20,000 (such as blankets, utensils, and domestic animals), the Native American tribes ceded to the United States large parts of modern-day Ohio, the future site of downtown Chicago,[nb 1][4] the Fort Detroit area, the Maumee, Ohio Area,[5] and the Lower Sandusky, Ohio Area.[6]

The United States was represented by General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, who led the victory at Fallen Timbers. Other Americans at the treaty include William Wells, William Henry Harrison, William Clark, Caleb Swan, and Meriwether Lewis.[7]

Native American leaders who signed the treaty included leaders of these bands and tribes: Wyandot chiefs Tarhe, Leatherlips, and Roundhead (Wyandot), Delaware (Lenape; several bands). Shawnee, Chief Blue Jacket, Ottawa (several bands), Chippewa, Potawatomi (several bands), Miami (several bands), Chief Little Turtle, Wea, Kickapoo, and Kaskaskia.[8]